Amdan/About Miniatures

"The hand being the measure of miniature”

Susan Stewart

This page gives some background to miniatures, some examples, their potential…

and what to avoid

Mae’r dudalen hon yn rhoi rhywfaint o gefndir i weithio ar raddfa fach, enghreifftiau,

eu potensial…a beth i’w osgoi

Miniatures as physical objects

Physical miniatures offer a playful way to imagine, play and experiment. They appear in all sorts of cultural forms - from the rich non-Western tradition of experiments with scale and the fantastic, such as the Japanese netsuke, the Persion and Indian miniatures, the miniature forms of Somali poetry, to the Saatchi-ready work of Jake and Dinas Chapman to the ‘craft’ traditions eg gardens on a plate competitions at agricultural shows, or ‘hobby’ type miniatures of model railway enthusiasts or ‘childhood play’ miniatures such as dolls houses:

Layla-Majnun is a Persian tale of love similar to Romeo and Juliet.

Christina Preis, Just Working in the Greenhouse

But the idea of the miniature is not without its problems. A search for ‘miniatures’ on ebay returns a terrifying number of pages for things with which to make war-scenes, and on facebook, numerous groups presenting (in our mind at least) horribly romantic notions of middle-class white ‘English’ home and historically-focused pastoral scenes. We are keen to avoid what Susan Stewart (in her wonderful book recommended to me by Chris. Dugrenier, ‘On Longing - narratives on the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection’) calls

“the social disease of nostalgia: We cannot separate the function of the miniature from a nostalgia for preindustrial labour, a nostalgia for craft”.

We would like Utopias Bach to be a forward looking, revolutionary even. Is it possible to create miniatures of alternative futures for our industrial/neoliberal state without being nostalgic? We think we’ll have to find a way of ‘breaking’ of some of the Western/British traditions/associations of miniatures such as the depiction of self contained and/or privileged worlds (could they be conceived with messy boundaries, depending others for completion?); or unquestioned mainstream cultural assumptions and formulations (seeking diversity is essential); a generalisation or idealisation (could ‘milltir sgwâr counter this?); or the assumption of anthropocentric universe for its absolute sense of scale (what of non-human view). We’d also like to challenge the idea that some ‘types’ of miniature are for a particular type of person, for example, the caption under the garden on a plate image above read:

“A miniature scene on a plate, part of the kids section – one of my favourite classes, if only I was still little, I’d love to enter this class.”

Image: Revolutionary Garden on a Plate: Gardd yr Heneb Ddiangen: The Garden of the Unwanted Monument, Lindsey Colbourne 2020

Non-physical Miniatures

“the miniature is the notation of the moment and the moment’s consequences”

- Susan Stewart

What of thinking about the ‘no place’ aspect of Utopia (which is what Utopia literally means!), in the context of miniature? How might a conversation, a shared meal, a network, a set of relationships, a system of learning be a miniature - as in a microcosm? Perhaps the process of thinking about and creating a physical miniature and discussing the issues it raises could itself be a miniature process?

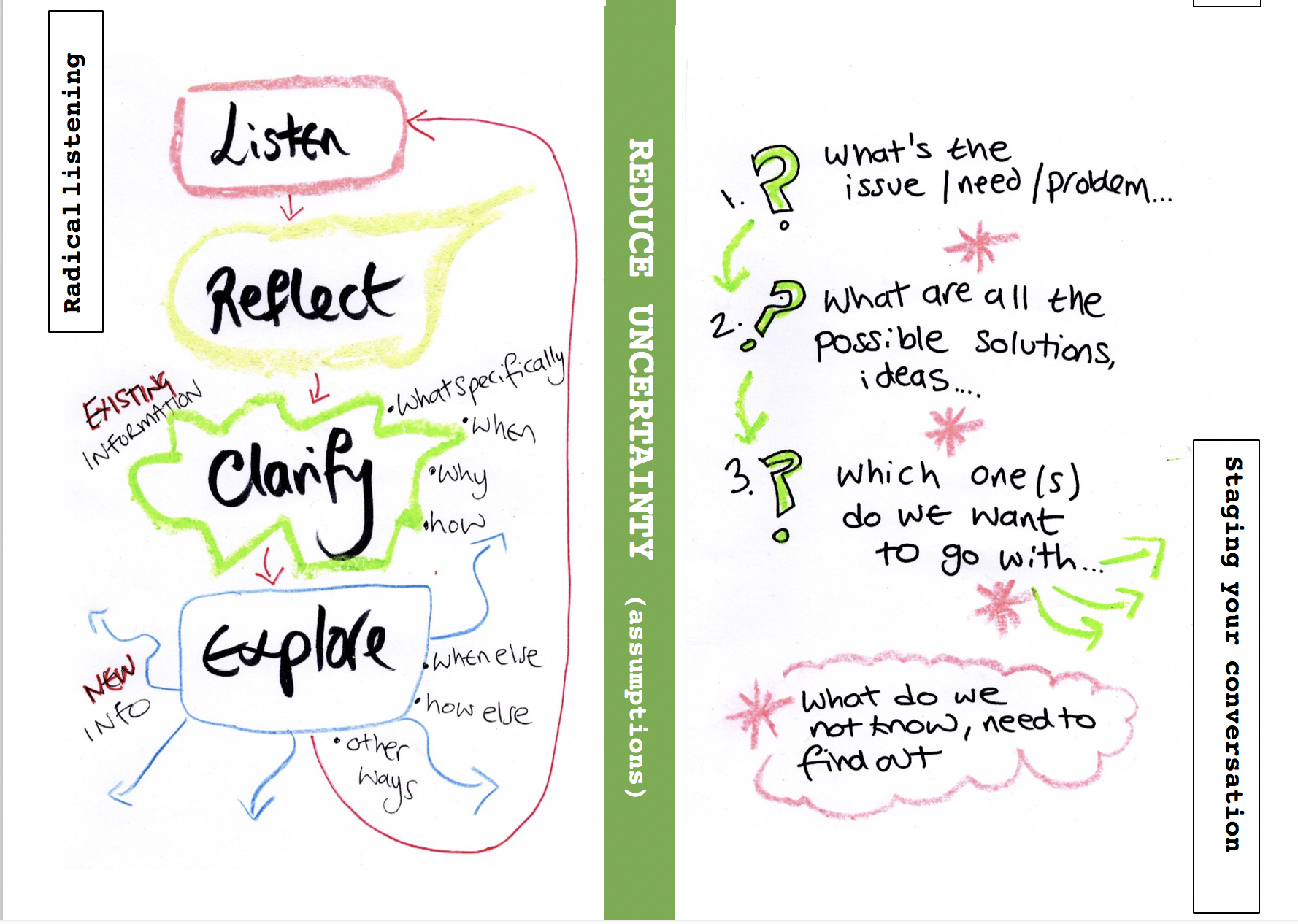

Here’s an example of a radical model of listening, that we tried out at Gwyl Gwrthsafiad Resistance Festival in Croesor (February 2020): Using this framework, we created a miniature of a new way of interacting with each other, a Utopia bach within the wider world of polarisation and ‘positional arguing’ of social media…

Many of our experiments are turning out to be non-physical miniatures, see here

Types of physical miniatures

(and their evolution)

“Realistic portraits of people and landscapes (which are essentially portraits of nature) do not, as a general rule, provide apt material for much in little. The basic purpose of both is likeness, and true likeness precludes imaginative variation. Specific detail is documentary, referring to the one and not to the many” - Carl Zigrosser

Micrographia - tiny books. and calendars and almanacs. The earliest small book was the Diurnale Moguntinum, printed by Peter Schoeffer in Mainz in 1468. The invention of printing coincided with the invention of childhood and the two faces of children’s literature, the fantastic and the didactic developed at the same time as the miniature book. The smallest printed book in the world, Eben Francis Thompson’s edition of ‘The Rose Garden of Oma Khayyám’ (3/16 by 5/16 of an inch) followed Meig’s attempt to collapse the significance of of the Orient into the exotica of a miniaturised volume: The miniature book always calls attention to the the book as a total object.

Miniature Calendar by Tanaka Tatsuya

Multum in parvo - “much in little; a great deal in a small space or in brief.” the miniaturisation of language itself in quotation, epigram and proverb, free-floating pieces of discourse abstacted from the context in hand in such a way as to transcend lived experience and speak to all times and places. Visual and linguistic multum in parvo is best shown in display mode; hence its place on home samplers has now been taken over by posters, cards, bumper stickers and t-shirts… eg (currently): Daw eto haul ar fryn, and a phrase I overheard on Resonance FM the other day “Some of my best friends have stems”… And what of the miniature sci-fi novel??

Dolls houses. There be danger here as doll houses can be motifs of wealth and nostalgia (displaying ‘good taste’, ‘order’ and a panoply of objects for consumption), transcending history and narrative… “We might suspect [these] as monuments against instability, randomness and vulgarity, speaking of all the class relations that are absent from its boundaries” - Susan Stewart. By contrast see these miniature houses for street mice, which have a serious message!

Portraits. Portrait miniatures first appeared in the 1520s, at the French and English courts. The earliest examples were painted by two Netherlandish miniaturists, Jean Clouet working in France and Lucas Horenbout in England. These were often used as symbols of loyalty to the crown, and in the 18th Century started to be painted on Ivory and businesses were set up in India (with permission from the East India Company) to paint local dignitaries, most of whom were British. So miniature portraits have a pretty grim close association with imperialism.

Photos. Potential for playing with scale and time. Photos of miniature scenes or more-than-human tiny worlds. Miniature photos of huge things rendered (im)possible (depending on whether your utopia would unleash/control).

Toys, automatia, dolls. Physical embodiments of fiction, devices for fantasy, a point of beginning for narrative. Once the toy becomes animated (by interacting with it), it initiates another world, the world of the daydream (an entirely new temporal world). Dangers here are impossibility of the daydream world to intersect with everyday reality eg an automata speaks to a repetition and closure that everyday world finds impossible….

Online: Perhaps Minecraft, and during lockdown, Animal Crossing, could be considered spaces in which to create miniature worlds… they could be considered dioramas? But also see dangers of automatia above

Dioramas. Originally these were mobile theatre devices, created by Daguerre and Bouton in the 1820s in France. They consisted of a piece of material painted on both sides. When illuminated from the front, one scene would be visible, and from the back, another (potential here!). A miniature diorama now tends to refer to a partially 3-D model, using scale models and landscaping to create a realistic scenario eg events, biomes, cultural scenes etc. They often combine a trompe-l’oeil in the background with 3D models in the foreground, but also little scenes made in shoe-boxes/Lego/gardens on a plate would be miniature dioramas. Dioramas make it easy to think of the scene coming alive, as in The Night at the Museum.

Image: Lisa Hudson, 2021